What are True Peaks?

Introduction

You’re in all probability aware of peak meters. They’re in each DAW, they usually let you understand when your mix is clipping. “Clipping” occurs when your mix is just too loud. The music’s volume will get automatically turned down. The louder components are clipped off, decreasing the dynamic range and creating distortion.

Peak meters are supposed to indicate where your music will clip. However, in actuality, common peak meters aren’t at all times correct. They miss some peaks that may occur when your music is translated from digital data into actual sound.

That’s the place true peak meters come in. True peak meters present all the peaks, together with ones that may happen when your music is converted into audio. When checking your mixes and masters for undesirable peaks, it’s best to use a true peak meter at all times.

What are True Peaks?

DAWs measure volume utilizing what’s referred to as a sample peak program meter. The meters we see in our digital mixer present us values in dBFS, and the utmost level attainable in a digital system is 0dBFS. Common sense tells us that as long as we hold our most values at or beneath 0dBFS, we are able to keep away from clipping, which causes audible distortion and different nasty-sounding business in our recordings. In the real world, it’s more difficult than that.

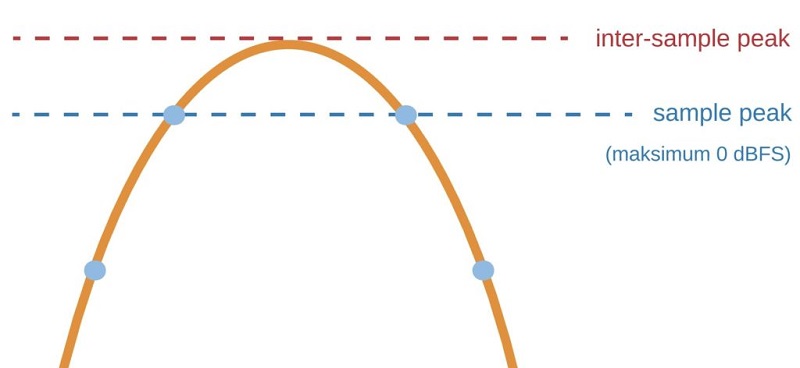

Digital recording takes an analog signal, then converts it to a digital one which’s saved on the pc. It captures thousands of samples per second, as decided by the sample rate, to recreate the analog signal. The dBFS meters within the DAW measure the peak values of those samples as they exist within the digital area. Nevertheless, they don’t tell us the true peak values.

Through the D/A conversion process, as a digital signal will get reconstructed again to an analog one for playback, there might be slight variations in level. The analog reconstruction of the signal can really peak well above the utmost digital sample value. When that occurs, we name it a true peak or an inter-sample peak.

Common meters and limiters don’t detect true peaks, and thus audio that exceeds 0dBFS may very well be stepping into your finished mixes. Within the studio listening back via decent converters, you won’t discover it. However, as soon as the file leaves the DAW and will get performed back on someone else’s system, digital clipping could also be obvious. It’s all the worse when changing mixes to lossy codecs like MP3.

What is Loudness?

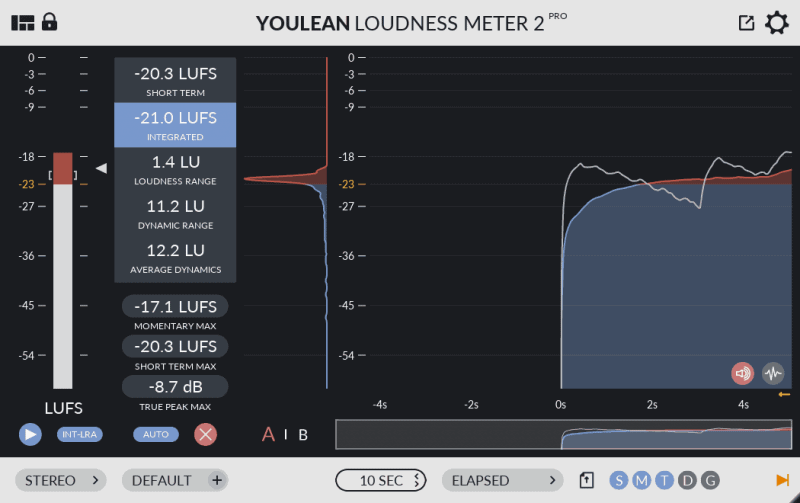

Loudness – may be extra precisely known as “perceived” loudness or “apparent” loudness – is measured in LUFS (typically known as LKFS), and is at all times measured over a period of time. LUFS makes use of the identical relative scale as decibels.

The loudness of a whole program or music is named integrated loudness. A lot of the time, when we speak about “loudness” we imply integrated loudness. There’s additionally short-term loudness, momentary loudness, and LRA (often known as loudness range), however, these are much less necessary, so for this blog, you’ll be able to assume we are referring to integrated loudness!

The ITU BS.1770 recommendation is the worldwide normal for measuring loudness and is used as a foundation for the ATSC A/85 used for television within the USA, the EBU R-128 which is utilized in most of Europe, and numerous different loudness specifications.

BS.1770 takes into consideration issues just like the acoustic effects of the human head, so totally different frequency ranges are weighted otherwise. The newest ITU revision is BS. 1770-4, but earlier revisions are nonetheless utilized in some circumstances – for instance, components of Netflix’s loudness specification refer to BS. 1770-1.

How are they connected?

A standard misconception is that loudness and True Peak are depending on one another, however, this isn’t the case. It’s possible, for instance, for a chunk of audio to have a maximum True Peak measurement effectively beneath spec, however for its integrated loudness to be a number of LKFS above target. A special piece of audio with the very same integrated loudness may have a lot larger maximum True Peak value.

One of the best explanations for that is that True Peak is an absolute ceiling, whereas integrated loudness is an average measurement of your complete music or program. In case your True Peak level goes above the target value even once, at actually any point, then the maximum True Peak on your total project can be above spec.

However, you may have a number of sections that, if measured individually, are “louder” than the target value, without the general value essentially going above spec.

True Peak Limiter

Most meters and limiters only present us sample peaks; that’s, the utmost worth of the digital samples making up the recorded analog signal. These don’t account for true peak values that happen as soon as the digital signal is reconverted back to an analog one.

The simplest technique to keep away from inter-sample clipping attributable to D/A conversion is by utilizing true peak meters and/or true peak limiters. A true peak meter can present us with inter-sample peak values; a true peak limiter can pick them out and ensure they don’t clip. Loudness specs for post-production and broadcast normally include a strict requirement that this system is mixed to true peak ranges, not simply sample peak levels.

In music, loudness specs are much less strict, nevertheless, it’s a good suggestion to know true peak ranges and the way they will probably degrade your mix relying on where it ends up. Some of us would argue that inter-sample peaks are virtually unnoticeable. Due to the so-called ‘loudness wars,’ some huge hits are mastered between +1 and +3dBTP (decibel true peak).

True Peak when Mastering

When mastering audio, it’s a widespread practice to set the limiter at 0dBFS and push the audio hard into it. The aim is normally to get the track sounding as LOUD as possible to compete with all the other very loud tracks on the charts.

This method will inevitably trigger the audio to clip on many playback systems because of the digital to analog conversion. It’s identified that almost all of the chart hits through the ‘Loudness Wars’ years have a real peak around +1dBTP (decibels true peak) and up to +3dBTP (that’s a lot of distortion).

Some folks argue that these inter-sample peaks are so unnoticeable that they don’t deserve our consideration. Nevertheless, inter-sample peaks are distorting the audio we hear. Would it not be better to master audio with a barely lower peak and easily take away this distortion? An excellent true peak meter offers you a correct studying of your audio’s peak level. By mastering 0dBTP you’ll give your viewers the very best listening experience.

Conclusion

So, whenever you use normalization for digital recording, don’t pressure it at all. Any audio editor permits normalization, however, we take pointless risks after we ask you to set the height at full scale, leaving the brand new peak at 0dBFS in order that the very best sample is on the end of its path.

The best suggestion is to remain barely lower when normalizing, even when it’s as little as one decibel. And now we perceive one of many reasons. When the normalization software prompts you to set the brand new peak value to 0dBFS, tempting as it sounds, you should at all times include a small gap.